As anyone left stunned after an encounter with Borges’s “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” or Kafka’s “A Country Doctor” will testify, well-executed high-concept short fiction can be a powerful force.

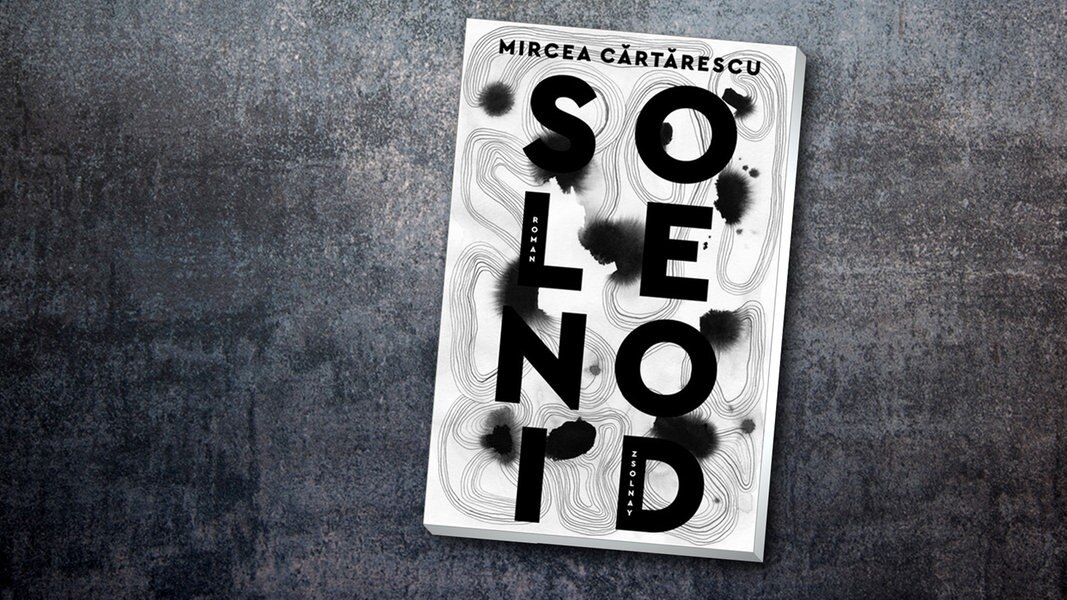

For how can one deny the case for narrative concision made by Kafka’s best stories or Borges’s corpus? The stories of the classic 20th-century dream weavers knock readers out of balance with everyday reality, only to hustle them, still dazed, out of the textual and back into the real world. Borges’s maxim expresses a kind of anxiety every reader must contend with before committing to such a mammoth text: is reading this going to be worth the effort? And, especially in the domain of surrealist literature, the question seems especially apropos. Romanian surrealist Mircea Cărtărescu is an avowed devotee of Borges, though his novel Solenoid - released in English in October by Deep Vellum Press (translated by Sean Cotter) - is a vast book, not just 500 pages, but significantly more. (Oct.IN THE INTRODUCTION to the 1941 publication of his The Garden of Forking Paths, Jorge Luis Borges famously contends that “it is a laborious madness and an impoverishing one, the madness of composing vast books - setting out in five hundred pages an idea that can be perfectly related orally in five minutes.” This scabrous epic thrums with monstrous life. For the reader, it’s more than a rewarding quest. Behind the narrator’s torrential output is a deep Kafkaesque desire to solve an impossible puzzle. His search is aided, or frustrated, by baffling signs and visions proliferating across Bucharest, which the narrator struggles to decode and which produce fascinating digressions into the mystical origins of the Rubik’s cube and an “incomprehensible, monstrous” medieval manuscript.

The novel shuttles among drily grotesque evocations of the narrator’s life, his phantasmagoric dreams, and his obsessive search-along with a group of anti-death advocates called The Picketists-for a portal through which to escape the terrestrial plane. The unnamed narrator has abandoned his youthful aspirations to become a writer, though he zealously maintains a diaristic “report of anomalies.” He languishes in obscurity as an elementary school teacher in Bucharest, which he calls “a museum of melancholy and the ruin of all things.” Bookish and febrile, he lives in a boat-shaped house built atop one of the city’s five “solenoids,” torus-shaped metallic structures that tap into the energy of the fourth dimension, as well as providing earthly benefits such as the ability to levitate during sex. Cartarescu ( Blinding) weaves a monumental antinovel of metaphysical longing and fabulist constructions.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)